Rewia

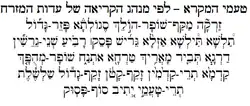

Rewia oder (Munach)-Rewi’i ֗(hebräisch רְבִ֗יע)[1] ist eine Trope (von jiddisch טראָפּ trop)[2] in der jüdischen Liturgie und zählt zu den biblischen Satz-, Betonungs- und Kantillationszeichen Teamim, die im Tanach erscheinen.

| Betonungszeichen oder Akzent Unicodeblock Hebräisch | |

|---|---|

| Zeichen | ֗ |

| Unicode | U+0597 |

| (Munach-)Rewi’i | מונח רְבִ֗יע |

| Rewia | רְבִ֗יעַ |

| Rawia | רָבִ֗יעַ |

Symbol

| Rewia | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Biblische Betonungszeichen | |||||||

| Sof pasuq | ֽ ׃ | Paseq | ׀ | ||||

| Etnachta | ֑ | Segol | ֒ | ||||

| Schalschelet | ֓ | Zakef katan | ֔ | ||||

| Zakef gadol | ֕ | Tipcha | ֖ | ||||

| Rewia | ֗ | Zinnorit | ֘ | ||||

| Paschta | ֙ | Jetiw | ֚ | ||||

| Tewir | ֛ | Geresch | ֜ | ||||

| Geresch muqdam | ֝ | Gerschajim | ֞ | ||||

| Qarne para | ֟ | Telischa gedola | ֠ | ||||

| Pazer | ֡ | Atnach hafuch | ֢ | ||||

| Munach | ֣ | Mahpach | ֤ | ||||

| Mercha | ֥ | Mercha kefula | ֦ | ||||

| Darga | ֧ | Qadma | ֨ | ||||

| Telischa qetanna | ֩ | Jerach ben jomo | ֪ | ||||

| Ole we-Jored | ֫ ֥ | Illuj | ֬ | ||||

| Dechi | ֭ | Zarqa | ֮ | ||||

| Rewia gadol | ֗ | Rewia mugrasch | ֜ ֗ | ||||

| Rewia qaton | ֗ | Mahpach legarmeh | ֤ ׀ | ||||

| Azla legarmeh | ֨ ׀ | Kadma we-asla | ֨ ֜ | ||||

| Maqqef | ־ | Meteg | ֽ | ||||

Das Symbol für Rewia ist in den Handschriften ein einfacher Punkt, wird aber in Druckausgaben meist rautenförmig wiedergegeben.[3] Wickes sieht in dem einen Punkt von Rewia ein System, wobei es vom stärkeren Trenner Zakef mit zwei Punkten und dieses wiederum vom noch stärkeren Segol mit drei Punkten übertroffen wird.[4]

Beschreibung

Die Trope ist ein disjunktiver Akzent der dritten Ebene. Rewia erscheint vor Paschta-, Tewir- oder Zarka-Segmenten, ist aber stärker als Paschta, Tewir oder Zarqa.[5]

Kombinationsmöglichkeiten

| Rewia | Munach | Darga | Munach |

|---|---|---|---|

| ֗ | ֣ | ֧ | ֣ |

Rewia steht häufig alleine. Wenn das vorhergehende Wort sich in der Bedeutung auf das Wort mit Rewia bezieht, dann wird es mit einem Verbinder, wie z. B. Munach, gekennzeichnet. Wenn ein weiterer konjunktiver Akzent vor Munach erscheint, dann ist es Darga. Es kann noch eine weitere konjunktive Trope Munach vor Darga erscheinen.[6]

| Rewia | Munach | (Munach)-Legarmeh | Mercha |

|---|---|---|---|

| ֗ | ֣ | ׀ ֣ | ֥ |

Wenn sich die vorhergehenden Worte in der Bedeutung auf das Wort mit Rewia beziehen, dann werden sie es mit Verbindern, wie z. B. Munach, gekennzeichnet. Manchmal geht jedoch ein disjunktiver Akzent voraus: Munach-Legarmeh, der bis auf wenige Ausnahmen nur in Rewia-Segmenten auftaucht. Es kann davor ein weiterer konjunktiver Akzent Mercha hinzutreten.[7] Rewia kann auch ein vorhergehendes disjunktives Geresch-Segment haben, welches alleine oder vor einem zwischengeschobenen Munach-Legarmeh-Segment auftauchen kann.[8]

Vorkommen

Die Tabelle zeigt das Vorkommen von Rewia in den 21 Büchern.[9]

| Teil des Tanach | Rewia |

|---|---|

| Tora | 2430 |

| Vordere Propheten | 2569 |

| Hintere Propheten | 2239 |

| Ketuvim | 1672 |

| Gesamt | 8910 |

Literatur

- Francis L. Cohen: Cantillation. In: Isidore Singer (Hrsg.): The Jewish Encyclopedia. Band III. KTAV Publishing House, New York 1902, S. 542–548 (de.scribd.com).

- William Wickes: A treatise on the accentuation of the three so-called poetical books on the Old Testament, Psalms, Proverbs, and Job. 1881 (archive.org).

- William Wickes: A treatise on the accentuation of the twenty-one so-called prose books of the Old Testament. 1887 (archive.org).

- Arthur Davis: The Hebrew accents of the twenty-one Books of the Bible (K"A Sefarim) with a new introduction. 1900 (archive.org).

- Solomon Rosowsky: The Cantillation of the Bible. The Five Books of Moses. The Reconstructionist Press, New York 1957.

- Israel Yeivin: Introduction to the Tiberian Masorah. Hrsg.: E. J. Revell. Scholars Press, Missoula, Montana 1980, ISBN 0-89130-374-X.

- Joseph Telushkin: Jewish literacy: the most important things to know about the Jewish religion, its people, and its history. W. Morrow, New York City 1991, OCLC 22703384.

- Louis Jacobs: The Jewish Religion: A Companion. Oxford University Press, Oxford / New York 1995, OCLC 31938398.

- James D. Price: Concordance of the Hebrew accents in the Hebrew Bible. (Vol. I). Concordance of the Hebrew Accents used in the Pentateuch. Edwin Mellon Press, Lewiston (New York) 1996, ISBN 0-7734-2395-8.

- Arnold Rosenberg: Jewish Liturgy As A Spiritual System: A Prayer-by-Prayer. Explanation Of The Nature And Meaning Of Jewish. Jason Aronson, Northvale 1997, OCLC 35919245.

- Page H. Kelley und Daniel S. Mynatt und Timothy G. Crawford: The Masorah of Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia: introduction and annotated glossary. W.B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, Grand Rapids (Michigan) 1998, OCLC 38168226.

- Marjo Christina Annette Korpel und Josef M. Oesch: Delimitation criticism. a new tool in biblical scholarship. Van Gorcum, Assen 2000, ISBN 90-232-3656-4.

- Joshua R. Jacobson: Chanting the Hebrew Bible. The art of cantillation. 1. Auflage. Jewish Publication Society, Philadelphia 2002, ISBN 0-8276-0693-1.

- Joshua R. Jacobson: Chanting the Hebrew Bible. Student Edition. The Jewish Publication Society, Philadelphia 2005, ISBN 0-8276-0816-0 (books.google.co.uk).

Weblinks

Einzelnachweise

- Joshua R. Jacobson: Chanting the Hebrew Bible. The art of cantillation. Jewish Publication Society. Philadelphia 2002, ISBN 0-8276-0693-1, S. 407, 936.

- Jacobson (2002), S. 3: Trop. «In Yiddish, the lingua franca of the Jews in Northern Europe […], these accents came to bei known as trop. The derivation of this word seems to be from the Greek tropos or Latin tropus ».

- Marshall Portnoy, Josée Wolff: The Art of Cantillation, Volume 2: A Step-By-Step Guide to Chanting Haftarot …. S. 43.

- William Wickes: A treatise on the accentuation of the twenty-one so-called prose books of the Old Testament. S. 16–17 (Textarchiv – Internet Archive).

- Jacobson (2005), S. 63 f.

- Jacobson (2005), S. 64.

- Jacobson (2005), S. 66 f.

- Price, Band 1, S. 189 f.

- James D. Price: Concordance of the Hebrew accents in the Hebrew Bible: Concordance …. 1. Band, S. 5.