Antimikrobielle Peptide

Antimikrobielle Peptide (auch Abwehrpeptide) sind Peptide, die antimikrobielle Eigenschaften aufweisen.

Eigenschaften

Antimikrobielle Peptide kommen in allen Reichen des Lebens vor. Bisher wurden über 1200 Peptide mit antimikrobieller Wirkung beschrieben.[1] Sie dienen der Abwehr einer Infektion mit Mikroorganismen. Die Wirksamkeit erstreckt sich auf Gram-negative und Gram-positive Bakterien, behüllte Viren, Pilze und Tumorzellen.[2] Im Gegensatz zu manchen Antibiotika ist die Wirkung gegen Bakterien bakterizid, nicht bakteriostatisch.[2] Als Maß für die Wirksamkeit dient die minimale Hemmkonzentration.[3] Antimikrobielle Peptide von Säugern besitzen zudem oftmals eine immunregulierende Wirkung.

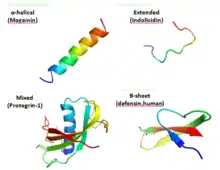

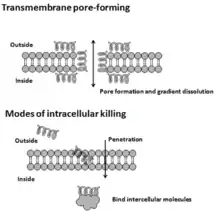

Antimikrobielle Peptide besitzen eine Länge zwischen 12 und 50 Aminosäuren. Sie werden nach ihrer Aminosäuresequenz in unterschiedliche Typen eingeteilt.[4] Meistens enthalten sie zwei oder mehrere positiv geladene Aminosäuren wie Lysin, Arginin und in saurer Umgebung auch Histidin. Weiterhin enthalten sie oftmals zu über 50 % hydrophobe Aminosäuren.[5][6][7] Aufgrund ihrer geringen Länge sind sie flexibel und nehmen ihre endgültige Konformation erst durch Protein-Lipid-Interaktionen bei der Bindung an eine Biomembran ein. Dabei sind die hydrophilen Aminosäuren zur wässrigen Seite hin ausgerichtet, die hydrophoben dagegen zu den Lipiden der Biomembran hin.[4] Manche antimikrobielle Peptide sind porenbildende Toxine, andere passieren zuerst die Biomembran und binden dann an ein zytosolisches Molekül,[8] z. B. bei der Proteinbiosynthese, der Proteinfaltung und der Synthese der Zellwand.[9]

Die selektive Wirkung gegen bakterielle Zellen und nicht gegen Säugerzellen entsteht unter anderem durch die enthaltenen positiv geladenen Aminosäuren, da die bakterielle Zellwand stärker negativ geladen ist als die Zellmembran von Säugern.[10] Weiterhin kommt Cholesterol nicht in bakteriellen Zellwänden vor, aber in Biomembranen von Säugern.[11] Daneben unterscheidet sich das Membranpotential.[12]

| Typ[13][14] | Eigenschaft | Beispiele |

|---|---|---|

| Schleifenförmige Peptide | reich an Glutaminsäure und Asparaginsäure, mit einer Disulfidbrücke | Maximin H5 aus Amphibien, Dermcidin des Menschen |

| Lineare α-helikale Peptide | ohne Cystein, amphipathisch | Cecropine, Andropin, Moricin, Ceratotoxin und Melittin aus Insekten, Magainin, Dermaseptin, Bombinin, Brevinin-1, Esculentine und Buforin II aus Amphibien, CAP18 aus Kaninchen, das Cathelicidin LL37 des Menschen, Pexiganan |

| Erweiterte Peptide mit Häufung einer Aminosäure | Prolin, Arginin, Phenylalanin, Histidin, Tryptophan | Abaecin, Apidaecine aus Honigbienen, Prophenin aus Schweinen, Indolicidin aus Kühen, Bac5, Bac7 |

| β-Faltblattpeptide mit 2 oder 3 Disulfidbrücken | 4 oder 6 Cysteine | 1 Brücke: Brevinine, 2: Protegrin aus Schweinen, Tachyplesine aus Pfeilschwanzkrebsen, 3: α-, β-Defensine des Menschen, >3: Drosomycin ais Fruchtfliegen |

Gegen verschiedene antimikrobielle Peptide wurden Resistenzmechanismen ausgebildet.[15][16][17][18][19][20]

Antimikrobielle Peptide sind unter anderem in den Datenbanken CAMP, CAMP release 2 (Collection of sequences and structures of antimicrobial peptides), Antimicrobial Peptide Database, LAMP, BioPD und ADAM (A Database of Anti-Microbial peptides) verzeichnet.

Anwendungen

Antimikrobielle Peptide werden, wie auch Bakteriophagen bei der Phagentherapie, zur Verwendung als topisch angewendete Biozide untersucht,[21] insbesondere zur Behandlung multiresistenter Krankheitserreger[22] und zur Behandlung von Haut- und Wundinfektionen.[23] Jedoch kann im Gegensatz zur Antibiotikaresistenz eine eventuell bei Bakterien entstehende Resistenz gegen antimikrobielle Peptide zu einer weniger effektiven Immunreaktion durch körpereigene antimikrobielle Peptide führen, während Antibiotika nicht vom Menschen gebildet werden.[24] Weiterhin werden sie aufgrund ihrer zytolytischen Eigenschaften zur Therapie von Tumoren untersucht.[25] Bei der Behandlung bakterieller Infektionen ist die selektive Zerstörung nur der bakteriellen Zellen erforderlich.[26]

Literatur

- E. M. Kościuczuk, P. Lisowski, J. Jarczak, N. Strzałkowska, A. Jóźwik, J. Horbańczuk, J. Krzyżewski, L. Zwierzchowski, E. Bagnicka: Cathelicidins: family of antimicrobial peptides. A review. In: Molecular biology reports. Band 39, Nummer 12, Dezember 2012, S. 10957–10970, doi:10.1007/s11033-012-1997-x. PMID 23065264, PMC 3487008 (freier Volltext).

- F. Desriac, C. Jégou, E. Balnois, B. Brillet, P. Le Chevalier, Y. Fleury: Antimicrobial peptides from marine proteobacteria. In: Marine drugs. Band 11, Nummer 10, Oktober 2013, S. 3632–3660, doi:10.3390/md11103632. PMID 24084784, PMC 3826127 (freier Volltext).

- J. P. Tam, S. Wang, K. H. Wong, W. L. Tan: Antimicrobial Peptides from Plants. In: Pharmaceuticals. Band 8, Nummer 4, 2015, S. 711–757, doi:10.3390/ph8040711. PMID 26580629.

- B. A. Katzenback: Antimicrobial Peptides as Mediators of Innate Immunity in Teleosts. In: Biology. Band 4, Nummer 4, 2015, S. 607–639, doi:10.3390/biology4040607. PMID 26426065, PMC 4690011 (freier Volltext).

- L. Martin, A. van Meegern, S. Doemming, T. Schuerholz: Antimicrobial Peptides in Human Sepsis. In: Frontiers in immunology. Band 6, 2015, S. 404, doi:10.3389/fimmu.2015.00404. PMID 26347737, PMC 4542572 (freier Volltext).

- H. Y. Yi, M. Chowdhury, Y. D. Huang, X. Q. Yu: Insect antimicrobial peptides and their applications. In: Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. Band 98, Nummer 13, Juli 2014, S. 5807–5822, doi:10.1007/s00253-014-5792-6. PMID 24811407, PMC 4083081 (freier Volltext).

Einzelnachweise

- T. Nakatsuji, R. L. Gallo: Antimicrobial peptides: old molecules with new ideas. In: Journal of Investigative Dermatology. Band 132, Nummer 3 Pt 2, 2012, S. 887–895, doi:10.1038/jid.2011.387. PMID 22158560, PMC 3279605 (freier Volltext).

- K. V. Reddy, R. D. Yedery, C. Aranha: Antimicrobial peptides: premises and promises. In: International journal of antimicrobial agents. Band 24, Nummer 6, Dezember 2004, S. 536–547, doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2004.09.005. PMID 15555874.

- D. Amsterdam: Susceptibility testing of Antimicrobials in liquid media. In: V. Lorian: Antibiotics in Laboratory Medicine. 4. Auflage. Williams and Wilkins, Baltimore, Md. 1996, S. 52–111.

- M. R. Yeaman, N. Y. Yount: Mechanisms of antimicrobial peptide action and resistance. In: Pharmacological reviews. Band 55, Heft 1, 2003, S. 27–55, doi:10.1124/pr.55.1.2. PMID 12615953.

- M. Papagianni: Ribosomally synthesized peptides with antimicrobial properties: biosynthesis, structure, function, and applications. In: Biotechnol Adv. Band 21, Heft 6, 2003, S. 465–499, doi:10.1016/S0734-9750(03)00077-6. PMID 14499150.

- N. Sitaram, R. Nagaraj: Host-defense antimicrobial peptides: importance of structure for activity. In: Current pharmaceutical design. Band 8, Nummer 9, 2002, S. 727–742. PMID 11945168.

- U. H. Dürr, U. S. Sudheendra, A. Ramamoorthy: LL-37, the only human member of the cathelicidin family of antimicrobial peptides. In: Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. Band 1758, Nummer 9, September 2006, S. 1408–1425, doi:10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.03.030. PMID 16716248.

- G. Wang, B. Mishra, K. Lau, T. Lushnikova, R. Golla, X. Wang: Antimicrobial peptides in 2014. In: Pharmaceuticals. Band 8, Nummer 1, 2015, S. 123–150, doi:10.3390/ph8010123. PMID 25806720, PMC 4381204 (freier Volltext).

- L. T. Nguyen, E. F. Haney, H. J. Vogel: The expanding scope of antimicrobial peptide structures and their modes of action. In: Trends in biotechnology. Band 29, Nummer 9, September 2011, S. 464–472, doi:10.1016/j.tibtech.2011.05.001. PMID 21680034.

- R. E. Hancock, H. G. Sahl: Antimicrobial and host-defense peptides as new anti-infective therapeutic strategies. In: Nature Biotechnology. Band 24, Nummer 12, Dezember 2006, S. 1551–1557, doi:10.1038/nbt1267. PMID 17160061.

- M. Zasloff: Antimicrobial peptides of multicellular organisms. In: Nature. Band 415, Nummer 6870, Januar 2002, S. 389–395, doi:10.1038/415389a. PMID 11807545.

- K. Matsuzaki, K. Sugishita, N. Fujii, K. Miyajima: Molecular basis for membrane selectivity of an antimicrobial peptide, magainin 2. In: Biochemistry. Band 34, Nummer 10, März 1995, S. 3423–3429. PMID 7533538.

- M. D. Seo, H. S. Won, J. H. Kim, T. Mishig-Ochir, B. J. Lee: Antimicrobial peptides for therapeutic applications: a review. In: Molecules. Band 17, Nummer 10, 2012, S. 12276–12286, doi:10.3390/molecules171012276. PMID 23079498.

- B. Mojsoska, H. Jenssen: Peptides and Peptidomimetics for Antimicrobial Drug Design. In: Pharmaceuticals. Band 8, Nummer 3, 2015, S. 366–415, doi:10.3390/ph8030366. PMID 26184232, PMC 4588174 (freier Volltext).

- S. Gruenheid, H. Le Moual: Resistance to antimicrobial peptides in Gram-negative bacteria. In: FEMS microbiology letters. Band 330, Nummer 2, Mai 2012, S. 81–89, doi:10.1111/j.1574-6968.2012.02528.x. PMID 22339775.

- J. L. Thomassin, J. R. Brannon, J. Kaiser, S. Gruenheid, H. Le Moual: Enterohemorrhagic and enteropathogenic Escherichia coli evolved different strategies to resist antimicrobial peptides. In: Gut microbes. Band 3, Nummer 6, Nov-Dez 2012, S. 556–561, doi:10.4161/gmic.21656. PMID 22895086, PMC 3495793 (freier Volltext).

- S. Ryu, P. I. Song, C. H. Seo, H. Cheong, Y. Park: Colonization and infection of the skin by S. aureus: immune system evasion and the response to cationic antimicrobial peptides. In: International journal of molecular sciences. Band 15, Nummer 5, 2014, S. 8753–8772, doi:10.3390/ijms15058753. PMID 24840573, PMC 4057757 (freier Volltext).

- S. L. Chua, S. Y. Tan, M. T. Rybtke, Y. Chen, S. A. Rice, S. Kjelleberg, T. Tolker-Nielsen, L. Yang, M. Givskov: Bis-(3'-5')-cyclic dimeric GMP regulates antimicrobial peptide resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. In: Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. Band 57, Nummer 5, Mai 2013, S. 2066–2075, doi:10.1128/AAC.02499-12. PMID 23403434, PMC 3632963 (freier Volltext).

- M. A. Campos, M. A. Vargas, V. Regueiro, C. M. Llompart, S. Albertí, J. A. Bengoechea: Capsule polysaccharide mediates bacterial resistance to antimicrobial peptides. In: Infection and immunity. Band 72, Nummer 12, Dezember 2004, S. 7107–7114, doi:10.1128/IAI.72.12.7107-7114.2004. PMID 15557634, PMC 529140 (freier Volltext).

- Catherine L. Shelton, Forrest K. Raffel, Wandy L. Beatty, Sara M. Johnson, Kevin M. Mason, H. Steven Seifert: Sap Transporter Mediated Import and Subsequent Degradation of Antimicrobial Peptides in Haemophilus. In: PLoS Pathogens. 7, 2011, S. e1002360, doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002360.

- G. Laverty, S. P. Gorman, B. F. Gilmore: The potential of antimicrobial peptides as biocides. In: International journal of molecular sciences. Band 12, Nummer 10, 2011, S. 6566–6596, doi:10.3390/ijms12106566. PMID 22072905, PMC 3210996 (freier Volltext).

- M. Malmsten: Antimicrobial peptides. In: Upsala journal of medical sciences. Band 119, Nummer 2, Mai 2014, S. 199–204, doi:10.3109/03009734.2014.899278. PMID 24758244, PMC 4034559 (freier Volltext).

- N. H. O'Driscoll, O. Labovitiadi, T. P. Cushnie, K. H. Matthews, D. K. Mercer, A. J. Lamb: Production and evaluation of an antimicrobial peptide-containing wafer formulation for topical application. In: Current microbiology. Band 66, Nummer 3, März 2013, S. 271–278, doi:10.1007/s00284-012-0268-3. PMID 23183933.

- M. G. J. L. Habets, M. A. Brockhurst: Therapeutic antimicrobial peptides may compromise natural immunity. In: Biology Letters. Band 8, Nummer 3, 2012, S. 416, doi:10.1098/rsbl.2011.1203.

- J. J. Guzmán-Rodríguez, A. Ochoa-Zarzosa, R. López-Gómez, J. E. López-Meza: Plant antimicrobial peptides as potential anticancer agents. In: BioMed research international. Band 2015, S. 735087, doi:10.1155/2015/735087. PMID 25815333, PMC 4359852 (freier Volltext).

- K. Matsuzaki: Control of cell selectivity of antimicrobial peptides. In: Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. Band 1788, Nummer 8, August 2009, S. 1687–1692, doi:10.1016/j.bbamem.2008.09.013. PMID 18952049.