MACPF

MACPF ist eine Familie von Proteinen, deren Vertreter eine MACPF-Proteindomäne besitzen. MACPF-Proteine sind z. B. C6, C7, C8α, C8β und C9 des membrane attack complex (MAC) des Komplementsystems und Perforin (PF), woher die Bezeichnung stammt. Sie dienen analog zu den porenbildenden Toxinen zur Bildung einer Pore in Bakterien, Pilzen, viral infizierten und entarteten Zellen im Rahmen der Immunantwort.[1][2]

Eigenschaften

MACPF-Proteine sind in verschiedenen Datenbanken registriert (Pfam= PF01823, InterPro= IPR001862, SMART= MACPF, PROSITE = PDOC00251, TCDB = 1.C.39). Das Protein C9 perforiert pathogene Gram-negative Bakterien und viral infizierte Zellen und führt somit zur Lyse und zum Zelltod.[3][4] Perforin wird von zytotoxischen T-Zellen freigesetzt und erlaubt zusätzlich zur Lyse den Einstrom von Granzymen in die zu lysierende Zelle.[3] Ein Gendefekt in einem der beiden Gene führt zu Erkrankungen.[5][6] MACPF sind von ihrer Proteinstruktur mit den cholesterolabhängigen Zytolysinen verwandt.[7][8]

Bisher wurden etwa 500 Vertreter der MACPF-Familie beschrieben. Im Menschen sind dies C6, C7, C8A, C8B, C9, FAM5B, FAM5C, MPEG1 und PRF1. Das pflanzliche Protein CAD1 dient ebenfalls der Infektabwehr.[9] Die Seeanemone Actineria villosa verwendet ein MACPF-Protein als Toxin.[10] MACPF-Proteine dienen der Plasmodium spp. zur Penetration der Zellen des Stechmückenwirts und der menschlichen Hepatozyten.[11][12]

Nicht alle MACPF-Proteine dienen der Abwehr. Astrotactin kommt bei der Zellmigration von Neuronen vor. Apextrin ist in der Entwicklung von Seeigeln beteiligt.[13][14] Das Torso-like protein in Drosophila steuert die embryonale Musterbildung.[15] Die Beteiligung einer möglichen lytischen Funktion dieser Proteine ist unbekannt.

Die MACPF-Proteine in Chlamydia spp. und in Photorhabdus luminescens wurden noch nicht näher charakterisiert.[16] Letzteres ist vermutlich nicht-lytisch.[7]

Struktur und Mechanismus

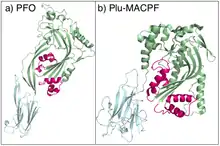

MACPF-Proteine sind von ihrer Proteinstruktur mit den cholesterolabhängigen Zytolysinen verwandt.[7][17] Die Proteinstruktur von Plu-MACPF, dem MACPF-Protein aus dem insektenpathogenen Enterobakterium Photorhabdus luminescens, ist homolog zu den porenbildenden Toxinen aus Clostridium perfringens. Die Konservierung der Aminosäuresequenz ist jedoch niedrig, weshalb der Nutzen sequenzbasierter Suchalgorithmen begrenzt ist.[7]

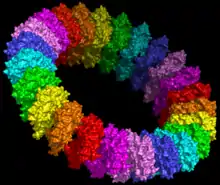

Vermutlich bilden MACPF-Proteine und cholesterolabhängige Zytolysine Poren über den gleichen Mechanismus.[7] Eine konzertierte Änderung der Proteinfaltung in jedem Monomer entwindet zwei α-Helices, woraus vier amphipathische β-Stränge gebildet werden, die die Zellmembran durchstoßen und die Pore in die Biomembran hinein erweitern.[7]

Modell basierend auf Pneumolysin.[19] |

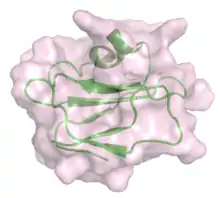

_with_bound_peptide_from_C8alpha_(cyan).png.webp) Kristallstruktur des C8γ (grün) mit einem Peptid von C8α (Cyan).[21] |

Erkrankungen

Gendefekte im C9 oder anderen Teilen des MAC erhöht das Risiko einer Meningokokken-Meningitis.[22] Eine übermäßige Aktivierung der MACPF-Proteine durch Mangel des Inhibitors CD59s führt zu paroxysmaler nächtlicher Hämoglobinurie.[23]

Eine Perforindefizienz führt zur hämophagozytischen Lymphohistiozytose (FHL oder HLH).[5][24]

Das MACPF-Protein DBCCR1 ist vermutlich ein Tumorsuppressor bei Blasenkrebs.[25]

Weblinks

Einzelnachweise

- Peitsch MC, Tschopp J: Assembly of macromolecular pores by immune defense systems. In: Curr. Opin. Cell Biol.. 3, Nr. 4, 1991, S. 710–6. doi:10.1016/0955-0674(91)90045-Z. PMID 1722985.

- Tschopp J, Masson D, Stanley KK: Structural/functional similarity between proteins involved in complement- and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-mediated cytolysis. In: Nature. 322, Nr. 6082, 1986, S. 831–4. doi:10.1038/322831a0. PMID 2427956.

- Voskoboinik I, Smyth MJ, Trapani JA: Perforin-mediated target-cell death and immune homeostasis. In: Nat. Rev. Immunol.. 6, Nr. 12, 2006, S. 940–52. doi:10.1038/nri1983. PMID 17124515.

- Kaiserman D, Bird CH, Sun J, et al.: The major human and mouse granzymes are structurally and functionally divergent. In: J. Cell Biol.. 175, Nr. 4, 2006, S. 619–30. doi:10.1083/jcb.200606073. PMID 17116752. PMC 2064598 (freier Volltext).

- Voskoboinik I, Sutton VR, Ciccone A, et al.: Perforin activity and immune homeostasis: the common A91V polymorphism in perforin results in both presynaptic and postsynaptic defects in function. In: Blood. 110, Nr. 4, 2007, S. 1184–90. doi:10.1182/blood-2007-02-072850. PMID 17475905.

- Witzel-Schlömp K, Späth PJ, Hobart MJ, et al.: The human complement C9 gene: identification of two mutations causing deficiency and revision of the gene structure. In: J. Immunol.. 158, Nr. 10, 1997, S. 5043–9. PMID 9144525.

- Rosado CJ, Buckle AM, Law RH, et al.: A Common Fold Mediates Vertebrate Defense and Bacterial Attack. In: Science. 317, Nr. 5844, 2007, S. 1548–1551. doi:10.1126/science.1144706. PMID 17717151.

- Michael A. Hadders, Dennis X. Beringer, and Piet Gros: Structure of C8-MACPF Reveals Mechanism of Membrane Attack in Complement Immune Defense. In: Science. 317, Nr. 5844, 2007, S. 1552–1554. doi:10.1126/science.1147103. PMID 17872444.

- Morita-Yamamuro C, Tsutsui T, Sato M, et al.: The Arabidopsis gene CAD1 controls programmed cell death in the plant immune system and encodes a protein containing a MACPF domain. In: Plant Cell Physiol.. 46, Nr. 6, 2005, S. 902–12. doi:10.1093/pcp/pci095. PMID 15799997.

- Oshiro N, Kobayashi C, Iwanaga S, et al.: A new membrane-attack complex/perforin (MACPF) domain lethal toxin from the nematocyst venom of the Okinawan sea anemone Actineria villosa. In: Toxicon. 43, Nr. 2, 2004, S. 225–8. doi:10.1016/j.toxicon.2003.11.017. PMID 15019483.

- Kadota K, Ishino T, Matsuyama T, Chinzei Y, Yuda M: Essential role of membrane-attack protein in malarial transmission to mosquito host. In: Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.. 101, Nr. 46, 2004, S. 16310–5. doi:10.1073/pnas.0406187101. PMID 15520375. PMC 524694 (freier Volltext).

- Ishino T, Chinzei Y, Yuda M: A Plasmodium sporozoite protein with a membrane attack complex domain is required for breaching the liver sinusoidal cell layer prior to hepatocyte infection. In: Cell. Microbiol.. 7, Nr. 2, 2005, S. 199–208. doi:10.1111/j.1462-5822.2004.00447.x. PMID 15659064.

- Zheng C, Heintz N, Hatten ME: CNS gene encoding astrotactin, which supports neuronal migration along glial fibers. In: Science. 272, Nr. 5260, 1996, S. 417–9. doi:10.1126/science.272.5260.417. PMID 8602532.

- Haag ES, Sly BJ, Andrews ME, Raff RA: Apextrin, a novel extracellular protein associated with larval ectoderm evolution in Heliocidaris erythrogramma. In: Dev. Biol.. 211, Nr. 1, 1999, S. 77–87. doi:10.1006/dbio.1999.9283. PMID 10373306.

- Martin JR, Raibaud A, Ollo R: Terminal pattern elements in Drosophila embryo induced by the torso-like protein. In: Nature. 367, Nr. 6465, 1994, S. 741–5. doi:10.1038/367741a0. PMID 8107870.

- Ponting CP: Chlamydial homologues of the MACPF (MAC/perforin) domain. In: Curr. Biol.. 9, Nr. 24, 1999, S. R911–3. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(00)80102-5. PMID 10608922.

- Michael A. Hadders, Dennis X. Beringer, and Piet Gros: Structure of C8-MACPF Reveals Mechanism of Membrane Attack in Complement Immune Defense. In: Science. 317, Nr. 5844, 2007, S. 1552–1554. doi:10.1126/science.1147103. PMID 17872444.

- Rossjohn J, Feil SC, McKinstry WJ, Tweten RK, Parker MW: Structure of a cholesterol-binding, thiol-activated cytolysin and a model of its membrane form. In: Cell. 89, Nr. 5, 1997, S. 685–92. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80251-2. PMID 9182756.

- Tilley SJ, Orlova EV, Gilbert RJ, Andrew PW, Saibil HR: Structural basis of pore formation by the bacterial toxin pneumolysin. In: Cell. 121, Nr. 2, 2005, S. 247–56. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.033. PMID 15851031.

- Kieffer B, Driscoll PC, Campbell ID, Willis AC, van der Merwe PA, Davis SJ: Three-dimensional solution structure of the extracellular region of the complement regulatory protein CD59, a new cell-surface protein domain related to snake venom neurotoxins. In: Biochemistry. 33, Nr. 15, 1994, S. 4471–82. doi:10.1021/bi00181a006. PMID 7512825.

- Lovelace LL, Chiswell B, Slade DJ, Sodetz JM, Lebioda L: Crystal structure of complement protein C8gamma in complex with a peptide containing the C8gamma binding site on C8alpha: Implications for C8gamma ligand binding. In: Molecular Immunology. 45, Nr. 3, 2007, S. 750–6. doi:10.1016/j.molimm.2007.06.359. PMID 17692377.

- Kira R, Ihara K, Takada H, Gondo K, Hara T: Nonsense mutation in exon 4 of human complement C9 gene is the major cause of Japanese complement C9 deficiency. In: Hum. Genet.. 102, Nr. 6, 1998, S. 605–10. doi:10.1007/s004390050749. PMID 9703418.

- Mark J. Walport: Complement. First of two parts. In: N. Engl. J. Med.. 344, Nr. 14, 2001, S. 1058–66. doi:10.1056/NEJM200104053441406. PMID 11287977.

- Verbsky JW, Grossman WJ: Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: diagnosis, pathophysiology, treatment, and future perspectives. In: Ann. Med.. 38, Nr. 1, 2006, S. 20–31. doi:10.1080/07853890500465189. PMID 16448985.

- Wright KO, Messing EM, Reeder JE: DBCCR1 mediates death in cultured bladder tumor cells. In: Oncogene. 23, Nr. 1, 2004, S. 82–90. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1206642. PMID 14712213.