Ranavirus

Ranavirus ist eine Gattung von Riesenviren (Nucleocytoviricota, NCLDVs) aus der Familie der Iridoviridae, Unterfamilie Alphairidovirinae.[2] Ranavirus ist die einzige Gattung in dieser Familie, deren Viren sowohl für Amphibien als auch Reptilien ansteckend sind. Wie auch die beiden anderen Gattungen Lymphocystivirus und Megalocytivirus der Unterfamilie Alphairidovirinae können Viren der Gattung Ranavirus auch Echte Knochenfische (Teleostei) infizieren.[3]

| Ranavirus | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

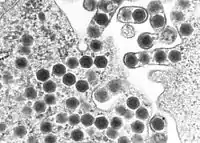

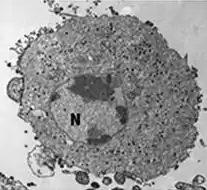

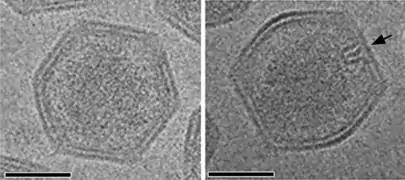

TEM-Aufnahme von Ranaviren | ||||||||||||||||||

| Systematik | ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Taxonomische Merkmale | ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Wissenschaftlicher Name | ||||||||||||||||||

| Ranavirus | ||||||||||||||||||

| Links | ||||||||||||||||||

|

Auswirkungen auf die Ökologie

Die Ranaviren sind wie die Megalocytiviren eine Gruppe eng verwandter dsDNA-Viren, deren Bedeutung immer mehr zunimmt. Sie verursachen systemische Erkrankungen bei einer Vielzahl von wilden und kultivierten Süß- und Salzwasserfischen. Wie bei Megalocytiviren sind Ranavirus-Ausbrüche in Aquakulturen von erheblicher wirtschaftlicher Bedeutung, da Tierseuchen zu beträchtlichem Verlust oder gar Massensterben von Zuchtfischen führen können. Im Gegensatz zu den Megalocytiviren wurden Ranavirus-Infektionen bei Amphibien als ein Faktor für den weltweiten Rückgang der Amphibienpopulationen in Betracht gezogen.[4][5] Der Einfluss von Ranaviren auf Amphibienpopulationen wurde mit dem des Chytridenpilz Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, dem Erreger der Chytridiomykose, verglichen.[6][7][8] Im Vereinigten Königreich wird angenommen, dass die Schwere der Krankheitsausbrüche aufgrund des Klimawandels (soll heißen: der globalen Erwärmung) zugenommen hat.[9]

Die Vorsilbe von lateinisch Rana ‚Frosch‘ abgeleitet[10] und erinnert an die erste Isolierung eines Ranavirus aus dem Nördlichen Leopardfrosch (Rana pipiens alias Lithobates pipiens) in den 1960er Jahren.[11][12][13]

Wirte

Von den folgenden Reptilienarten ist bekannt, dass sie Ranavirus infiziert werden können:

- Grüner Baumpython (Morelia viridis alias Chondropython viridis)[14]

- Burma-Landschildkröte (Geochelone platynota)

- Pantherschildkröte (Stigmochelys pardalis alias Geochelone pardalis)[15]

- Georgia-Gopherschildkröte (Gopherus polyphemus)

- Iberische Gebirgseidechse (Lacerta monticola)[16]

- Carolina-Dosenschildkröte (Terrapene carolina carolina)[17]

- Florida-Dosenschildkröte (Terrapene carolina bauri)

- (Westliche) Schmuck-Dosenschildkröte (Terrapene ornata)[18]

- Maurische Landschildkröte (Testudo graeca)[19]

- Griechische Landschildkröte (Testudo hermanni)

- Ägyptische Landschildkröte (Testudo kleinmanni)

- Vierzehenschildkröte alias Russische Landschildkröte (Testudo horsfieldii)

- Breitrandschildkröte (Testudo marginata)

- Rotwangen-Schmuckschildkröte (Trachemys scripta elegans)[18]

- Chinesische Weichschildkröte (Pelodiscus sinensis alias Trionyx sinensis)[20]

- Blattschwanzgeckos der Spezies Uroplatus fimbriatus[21]

Aufbau

Ranaviren sind große ikosaedrische DNA-Viren mit einem Durchmesser von etwa 150 nm und einem unsegmentierten linearen dsDNA-Genom von etwa 105 kbp,[22] Es gibt etwa 100 Proteine kodierende Gene.[23]

Das Genom von Frog virus 3 hat eine Länge von 105.903 bp und kodiert voraussichtlich 99 Proteine.[24]

Reproduktionszyklus

Die Replikation der Ranaviren ist bei der Typspezies Frog virus 3 (FV3) gut untersucht.

Die Replikation von FV3 erfolgt bei 12 bis 32 °C.[23]

Ranaviren gelangen durch Rezeptor-vermittelte Endozytose in die Wirtszelle.[25]

Die Viruspartikel (Virionen) sind unbeschichtet und wandern nach dem Eindringen durch die Endocytose in den Zellkern, wo die virale DNA-Replikation über eine viruskodierte DNA-Polymerase beginnt.[26]

Die Virus-DNA verlässt dann den Zellkern und es beginnt die zweite Stufe der DNA-Replikation im Zytoplasma, wobei letztendlich DNA-Concatemere gebildet werden.[26]

Die virale DNA wird dann in infektiöse Virionen verpackt.[27]

- Replikation am Beispiel von Frog virus 3 (FV3)

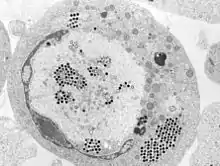

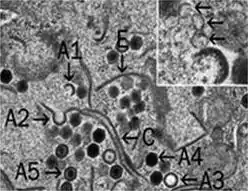

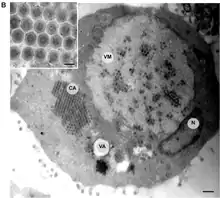

.jpg.webp) Transmissionselektronenmikroskop-Aufnahme einer mit ECV infizierten Zelle und (kleines Bild) knospenden FV3-Virionen

Transmissionselektronenmikroskop-Aufnahme einer mit ECV infizierten Zelle und (kleines Bild) knospenden FV3-Virionen FV3-infizierte Zelle, die Virionen sind über das Zytoplasma verteilt

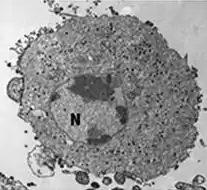

FV3-infizierte Zelle, die Virionen sind über das Zytoplasma verteilt FV3-infizierte Zelle mit Kern (N), Chromatinkondensation, viraler Assemblierungsstelle (AS), parakristallinen [en] Anordnungen (*) und knospenden Virionen (→).

FV3-infizierte Zelle mit Kern (N), Chromatinkondensation, viraler Assemblierungsstelle (AS), parakristallinen [en] Anordnungen (*) und knospenden Virionen (→). FV3-infizierte Zelle mit verstreuten Virionen

FV3-infizierte Zelle mit verstreuten Virionen viralen Assemblierungsstelle mit FV3-Virionen in verschiedenen Stadien der Assemblierung. Inset: Membranen (↗), evtl. aus dem ER.

viralen Assemblierungsstelle mit FV3-Virionen in verschiedenen Stadien der Assemblierung. Inset: Membranen (↗), evtl. aus dem ER.

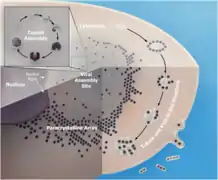

Auch die Spezies Singapore Grouper Iridovirus (SGIV), Erreger der Krankheit Singapore Grouper Iridovirus Disease (SGIVD)[28] beim Rostflecken-Zackenbarsch (Epinephelus tauvina, en. Greasy grouper [en])[29] ist inzwischen gut untersucht. Deren Viruspartikel werden in sog. viral assembly sites (VAS) zusammengebaut (assembliert).[30]

- Replikation am Beispiel von Singapore grouper iridovirus (SGIV)

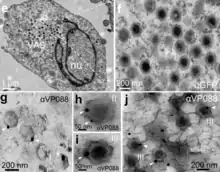

Replikationszyklus von SGIV innerhalb der Wirtszelle im Detail.-->

Replikationszyklus von SGIV innerhalb der Wirtszelle im Detail.--> Kapsid-Morphogenese von Singapore Grouper Iridovirus (SGIV) in einer viral assembly site (VAS)

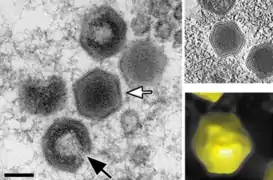

Kapsid-Morphogenese von Singapore Grouper Iridovirus (SGIV) in einer viral assembly site (VAS) Kryo-EM-Aufnahme von reifen SGIV-Virionen mit asymmetrischem haarnadelförmigen Komplex auf der einen Seite (schwarzer Pfeil). Für die Sichtbarkeit ist eine in geeignete Orientierung nötig.

Kryo-EM-Aufnahme von reifen SGIV-Virionen mit asymmetrischem haarnadelförmigen Komplex auf der einen Seite (schwarzer Pfeil). Für die Sichtbarkeit ist eine in geeignete Orientierung nötig. Virale Akkumulation von SGIV-Partikeln zu einer parakristallinen [en] Anordnung.

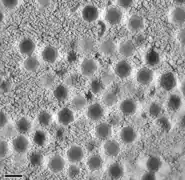

Virale Akkumulation von SGIV-Partikeln zu einer parakristallinen [en] Anordnung.

SGIV: Proteine verformen die Membran und bilden eine spezifische spiralförmige Struktur. Die Vakuolenmembran wird so zu einem Membrantubulus, der das Virion im Inneren der Vakuole enthält (Pfeile links).

SGIV: Proteine verformen die Membran und bilden eine spezifische spiralförmige Struktur. Die Vakuolenmembran wird so zu einem Membrantubulus, der das Virion im Inneren der Vakuole enthält (Pfeile links).

Das Genom von Ranavirus weist wie bei anderen Iridoviridae terminal redundante DNA auf.[26]

Es wird angenommen, dass die Übertragung von Ranaviren auf mehreren Wegen erfolgt, unter anderem über kontaminiertem Boden, direkten Kontakt, Exposition durch Wasser und Verschlucken von infiziertem Gewebe während der Jagd, Nekrophagie oder Kannibalismus. Ranaviren sind in Gewässern relativ stabil und können außerhalb eines Wirtsorganismus mehrere Wochen oder länger überdauern.[12]

Evolution

Die Ranaviren scheinen sich aus einem Fischvirus entwickelt zu haben, das anschließend Amphibien und Reptilien infizierte.[31]

Systematik

Die innere Systematik der Gattung Iridovirus ist mit Stand März 2021 nach ICTV, ergänzt um einige Vorschläge in doppelten Anführungszeichen (nach NCBI, wo nicht anders angegeben):[1]

- Familie: Iridoviridae

- Unterfamilie Alphairidovirinae

- Gattung: Ranavirus

- Spezies Ambystoma tigrinum virus (ATV)

- Spezies Common midwife toad virus (alias Common midwife toad ranavirus, CMTV)[32]

- Spezies Epizootic haematopoietic necrosis virus (alias Epizootic hematopoietic necrosis virus, EHNV)[30]

- European catfish virus (ECV)[36][37][35]

- European sheatfish virus (ESV), z. B. beim Europäischen Wels

- Spezies Frog virus 3 (Fv3, FV3, Typusspezies)

- Spezies Santee-Cooper ranavirus (SCRV)

Es gibt etliche nach ICTV mit Stand März 2021 noch nicht klassifizierten Kandidaten, siehe etwa Halaly et al. (2019).[34]

Einzelnachweise

- ICTV: ICTV Master Species List 2019.v1, New MSL including all taxa updates since the 2018b release, March 2020 (MSL #35)

- ICTV: Iridoviridae (en) In: ICTV Online (10th) Report.

- RJ Whittington, JA Becker, MM Dennis: Iridovirus infections in finfish – critical review with emphasis on ranaviruses. In: Journal of Fish Diseases. 33, Nr. 2, 2010, S. 95–122. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2761.2009.01110.x. PMID 20050967.

- A. G. F. Teacher, A. A. Cunningham, T. W. J. Garner: Assessing the long-term impact of Ranavirus infection in wild common frog populations: Impact of Ranavirus on wild frog populations. In: Animal Conservation. 13, Nr. 5, 10. Juni 2010, S. 514–522. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1795.2010.00373.x.

- Stephen J. Price, Trenton W. J. Garner, Richard A. Nichols, François Balloux, César Ayres, Amparo Mora-Cabello de Alba, Jaime Bosch: Collapse of Amphibian Communities Due to an Introduced Ranavirus. In: Current Biology. 24, Nr. 21, November 2014, S. 2586–2591. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2014.09.028.

- James K. Jancovich, Jinghe Mao, V. Gregory Chinchar, Christopher Wyatt, Steven T. Case, Sudhir Kumar, Graziela Valente, Sankar Subramanian, Elizabeth W. Davidson, James P. Collins, Bertram L. Jacobs: Genomic sequence of a ranavirus (family Iridoviridae) associated with salamander mortalities in North America. In: Virology. 316, Nr. 1, 2003, S. 90–103. doi:10.1016/j.virol.2003.08.001. PMID 14599794.

- Jesse L. Brunner, Danna M. Schock, Elizabeth W. Davidson, James P. Collins: Intraspecific Reservoirs: Complex Life History and the Persistence of a Lethal Ranavirus. In: Ecology. 85, Nr. 2, 2004, S. 560. doi:10.1890/02-0374.

- Pearman, Peter B., Trenton W. J. Garner: Susceptibility of Italian agile frog populations to an emerging strain of Ranavirus parallels population genetic diversity. In: Ecology Letters. 8, Nr. 4, 2005, S. 401. doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2005.00735.x.

- Stephen J. Price, William T. M. Leung, Christopher J. Owen, Robert Puschendorf, Chris Sergeant, Andrew A. Cunningham, Francois Balloux, Trenton W. J. Garner, Richard A. Nichols: Effects of historic and projected climate change on the range and impacts of an emerging wildlife disease. In: Global Change Biology. 9. Mai 2019, ISSN 1354-1013. doi:10.1111/gcb.14651.

- Harper, Douglas: ‚frog‘, in: Online Etymology Dictionary.

- A. Granoff, P. E. Came, K. A. Rafferty: The isolation and properties of viruses from Rana pipiens: their possible relationship to the renal adenocarcinoma of the leopard frog. In: Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 126, Nr. 1, 1965, S. 237–255. bibcode:1965NYASA.126..237G. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1965.tb14278.x. PMID 5220161.

- MJ Gray, DL Miller, JT Hoverman: Ecology and pathology of amphibian ranaviruses. In: Diseases of Aquatic Organisms. 87, Nr. 3, 2009, S. 243–266. doi:10.3354/dao02138. PMID 20099417.

- K. A. Rafferty: The cultivation of inclusion-associated viruses from Lucke tumor frogs. In: Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 126, Nr. 1, 1965, S. 3–21. bibcode:1965NYASA.126....3R. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1965.tb14266.x. PMID 5220167.

- Benetka V.: First report of an iridovirus (genus Ranavirus) infection in a leopard tortoise (Geochelone pardalis pardalis). In: Vet Med Austria. 94, 2007, S. 243–248.

- A. P. De Matos, M. F. Caeiro, T Papp, B. A. Matos, A. C. Correia, R. E. Marschang: New viruses from Lacerta monticola (Serra da Estrela, Portugal): Further evidence for a new group of nucleo-cytoplasmic large deoxyriboviruses (NCLDVs). In: Microscopy and Microanalysis. 17, Nr. 1, 2011, S. 101–108. bibcode:2011MiMic..17..101A. doi:10.1017/S143192761009433X. PMID 21138619.

- J Mao, RP Hedrick, VG Chinchar: Molecular characterization, sequence analysis, and taxonomic position of newly isolated fish iridoviruses. In: Virology. 229, Nr. 1, 1997, S. 212–220. doi:10.1006/viro.1996.8435. PMID 9123863.

- A. J. Johnson, A. P. Pessier, E. R. Jacobson: Experimental transmission and induction of ranaviral disease in Western Ornate box turtles (Terrapene ornata ornata) and red-eared sliders (Trachemys scripta elegans). In: Veterinary Pathology. 44, Nr. 3, 2007, S. 285–297. doi:10.1354/vp.44-3-285. PMID 17491069.

- Blahak S., Uhlenbrok C. "Ranavirus infections in European terrestrial tortoises in Germany". Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Reptile and Amphibian Medicine; Munich, Germany. 4–7 March 2010; pp. 17–23

- Z. X. Chen, J. C. Zheng, Y. L. Jiang: A new iridovirus isolated from soft-shelled turtle. In: Virus Research. 63, Nr. 1–2, 1999, S. 147–151. doi:10.1016/S0168-1702(99)00069-6. PMID 10509727.

- R. E. Marschang, S Braun, P Becher: Isolation of a ranavirus from a gecko (Uroplatus fimbriatus). In: Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine: Official Publication of the American Association of Zoo Veterinarians. 36, Nr. 2, 2005, S. 295–300. doi:10.1638/04-008.1. PMID 17323572.

- Williams T, Barbosa-Solomieu V, Chinchar GD: "A decade of advances in iridovirus research" S. 173-148. In: Maramorosch K, Shatkin A (Hrsg.): Advances in virus research, Vol. 65, Academic Press, New York, USA, 2005

- VG Chinchar: Ranaviruses (family Iridoviridae) emerging cold-blooded killers. In: Archives of Virology. 147, Nr. 3, 2002, S. 447–470. doi:10.1007/s007050200000. PMID 11958449.

- Disa Bäckström, Natalya Yutin, Steffen L. Jørgensen, Jennah Dharamshi, Felix Homa, Katarzyna Zaremba-Niedwiedzka, Anja Spang, Yuri I. Wolf, Eugene V. Koonin, Thijs J. G. Ettema; Richard P. Novick (Hrsg.): Virus Genomes from Deep Sea Sediments Expand the Ocean Megavirome and Support Independent Origins of Viral Gigantism, in: mBio Vol. 10, Nr. 2, März–April 2019, S. e02497-18, PDF, doi:10.1128/mBio.02497-18, PMC 6401483 (freier Volltext), PMID 30837339, ResearchGate

- Heather E. Eaton, Brooke A. Ring, Craig R. Brunetti: The genomic diversity and phylogenetic relationship in the family Iridoviridae. In: Viruses. 2, Nr. 7, 2010, S. 1458–1475. doi:10.3390/v2071458. PMID 21994690. PMC 3185713 (freier Volltext).

- R Goorha: Frog virus 3 DNA replication occurs in two stages. In: Journal of Virology. 43, Nr. 2, 1982, S. 519–528. PMID 7109033. PMC 256155 (freier Volltext).

- Chinchar VG, Essbauer S, He JG, Hyatt A, Miyazaki T, Seligy V, Williams T: "Family Iridoviridae" S. 145–162, in: Fauquet CM, Mayo MA, Maniloff J, Desselburger U, Ball LA (Hrsg.): Virus Taxonomy, Eighth report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses., Academic Press, San Diego, USA, 2005.

- Gilda D. Lio-Po, Leobert D. de la Peňa; Kazuya Nagasawa, Erlinda R. Cruz-Lacierda (Hrsg.): Diseases of Cultured Groupers, Southeast Asian Fisheries Development Center (SEAFDEC), Aquaculture Department, Government of Japan Trust Fund, Dezember 2004, ISBN 971-8511-70-9

- Virus-Host DB: Singapore grouper iridovirus

- Yang Liu, Bich Ngoc Tran, Fan Wang, Puey Ounjai, Jinlu Wu, Choy L. Hew: Visualization of Assembly Intermediates and Budding Vacuoles of Singapore Grouper Iridovirus in Grouper Embryonic Cells, in: Sci Rep 6, 18696, 4, Januar 2016, doi:10.1038/srep18696

- JK Jancovich, M Bremont, JW Touchman, BL Jacobs: Evidence for multiple recent host species shifts among the Ranaviruses (family Iridoviridae). In: J Virol. 84, Nr. 6, 2010, S. 2636–2647. doi:10.1128/JVI.01991-09. PMID 20042506. PMC 2826071 (freier Volltext).

- NCBI: Common midwife toad virus (species)

- Zhongyuan Chen, Jianfang Gui, Xiaochan Gao, Chao Pei, Yijiang Hong & Qiya Zhang: Genome architecture changes and major gene variations of Andrias davidianus ranavirus (ADRV), in: Veterinary Research Band 44, Nr. 101, 21. Oktober 2013, doi:10.1186/1297-9716-44-101

- Maya A. Halaly, Kuttichantran Subramaniam, Samantha A. Koda, Vsevolod L. Popov, David Stone, KeithWay, Thomas B. Waltzek: Characterization of a Novel Megalocytivirus Isolated from European Chub (Squalius cephalus), in: MDPI – Viruses 2019, 11, 440; doi:10.3390/v11050440, PDF

- Julien Andreani, Jacques Y. B. Khalil, Emeline Baptiste, Issam Hasni, Caroline Michelle, Didier Raoult, Anthony Levasseur, Bernard La Scola: Orpheovirus IHUMI-LCC2: A New Virus among the Giant Viruses, in: Front. Microbiol., 22. Januar 2018, doi:10.3389/fmicb.2017.02643

- Virus-Host DB: European catfish virus

- ICTV: European catfish virus, proposal 20162986

- Paul M. Hick, Kuttichantran Subramaniam Patrick Thompson Richard J. Whittington and Thomas B. Waltzekb: Complete Genome Sequence of a Bohle iridovirus Isolate from Ornate Burrowing Frogs (Limnodynastes ornatus) in Australia, in: Genome Announcv. 4(4); Juli-August 2016, PMC 4991696 (freier Volltext), PMID 27540051, doi:10.1128/genomeA.00632-16

- William H Wilson, Ilana C Gilg, Mohammad Moniruzzaman, Erin K Field, Sergey Koren, Gary R LeCleir, Joaquín Martínez Martínez, Nicole J Poulton, Brandon K Swan, Ramunas Stepanauskas, Steven W Wilhelm: Genomic exploration of individual giant ocean viruses, in: ISME Journal 11(8), August 2017, S. 1736–1745, doi:10.1038/ismej.2017.61, PMC 5520044 (freier Volltext), PMID 28498373

Weblinks

- ICTV: ICTV Online (10th) Report: Iridoviridae

- Expasy: Viralzone: Ranavirus

- Ranavirus-Net: Ranavirus Research Project

- Viral Diseases of Amphibians (viaWeb-Archiv)

- Herpetofauna Diseases, Southeast Partners in Amphibian and Reptile Conservation (SEPARC), Disease Task Team: Weitere Informationen zu Ranaviren und anderen Krankheitserregern, die die Amphibienpopulation beeinflussen, einschließlich des Chytridpilzes Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis und des ‚Salamanderfressers‘ Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans (Bsal).

- Chen Li, Liqun Wang, Jiaxin Liu, Yepin Yu, Youhua Huang, Xiaohong Huang, Jingguang Wei, Qiwei Qin: Singapore Grouper Iridovirus (SGIV) Inhibited Autophagy for Efficient Viral Replication, in: Front. Microbiol., Serie: Cell Organelle Exploitation by Viruses During Infection, 26. Juni 2020, oi:10.3389/fmicb.2020.01446