Kiril Pejtschinowitsch

Kiril Pejtschinowitsch (bulgarisch Кирил Пейчинович, altbulgarisch Күриллъ Пейчиновићь, mazedonisch Кирил Пејчиновиќ;* um 1770 in Tearce bei Tetovo, Osmanisches Reich, heute in Nordmazedonien; † 7. März 1845 im Kloster Lešok bei Tetovo) war ein bulgarischer Geistlicher, Schriftsteller und Aufklärer während der Zeit der Bulgarischen Wiedergeburt in Makedonien. Pejtschinowitsch war einer der ersten Unterstützer der modernen bulgarischen Sprache (im Gegensatz zum Kirchenslawischen) und neben Païssi von Hilandar und Sophronius von Wraza eine der ersten Figuren der bulgarischen Nationalen Wiedergeburt.[1][2][3]

Obwohl er sich und seine Sprache als Bulgarisch[4][5], den Begriff Makedonien vermied und die Region als Untermoesien bzw. Bulgarien bezeichnete[6][7], wird er nach der mazedonischen Geschichtsschreibung als ein ethnischer Mazedonier aufgefasst.[8][9][10] Da die meisten seiner Werke in seinem Heimatdialekt aus der Tetovo-Region im heutigen Staatsbegiet Nordmazedoniens verfasst wurden, wird im heutigen Nordmazedonien Pejtschinowitsch als einer der frühesten Mitwirkenden zur modernen mazedonischen Literatur angesehen. Dieses gilt jedoch als Versuch zeitgenössische ethnische Unterschiede in der Vergangenheit zu projizieren die zur Stärkung der mazedonischen Identität, auf Kosten der Bulgarischen führern soll.[11][12][13][14][15][16]

Leben

Frühes Leben und Hegumen in Klöster

Pejtschinowitsch wurde in Tearce im heutigen Nordmazedonien (damals Teil des Osmanischen Reiches) geboren. Sein weltlicher Name ist unbekannt. Laut seinem Grabstein erhielt er seine Grundschulbildung im Dorf Lešok bei Tetovo. Wahrscheinlich studierte er später im Kloster Sveti Jovan Bigorski bei Debar. Kirils Vater Pejtschin verkaufte seinen Besitz in Tearce und zog zusammen mit seinem Bruder und seinem Sohn in das Kloster Hilandar auf dem Berg Athos, wo die drei Mönche wurden. Pejtschin nahm den Namen Pimen an, seinen Bruder – Dalmant und seinen Sohn – Kiril. Später kehrte Kiril nach Tetovo zurück und machte sich auf den Weg zum Kloster Kičevo, wo er Priestermönch wurde.

Seit 1801 war Pejtschinowitsch der Hegumen des Marko-Klosters des Heiligen Demetrius in der Nähe von Skopje. Das Kloster liegt in der Region Torbešija entlang des Tals der Markova Reka (Markos Fluss) zwischen pomakischen, türkischen und albanischen Dörfern und befand sich vor Pejtschinowitschs Ankunft in einem miserablen Zustand. Fast alle Gebäude außer der Hauptkirche waren zerstört. Im Laufe von 17 Jahren bis 1798 bemühte sich Kiril ernsthaft um die Wiederbelebung des Klosters, wobei er besonderes Augenmerk auf den Wiederaufbau und die Erweiterung der Klosterbibliothek legte.

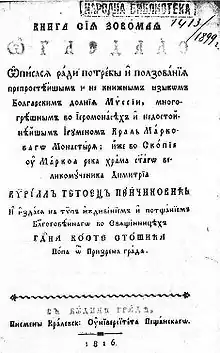

Im Marko-Kloster stellte Kiril Pejtschinowitsch eines seiner bekanntesten Werke zusammen, Ogledalo (zu dt. Spiegel), das 1816 in Budapest gedruckt wurde.

Es ist nicht bekannt, warum Kiril das Marko-Kloster verließ, aber der Legende nach war ein Konflikt zwischen ihm und dem griechischen Metropoliten Skopje der Grund für seine Abreise. Im Jahr 1818 reiste Pejtschinowitsch erneut auf den Berg Athos, um seinen Vater und seinen Onkel zu besuchen, und wurde dann Hegumen im Kloster Lešok (1710 von Janitscharen zerstört) in der Nähe des Polog-Dorfes Lešok, nahe seiner Heimat Tearce. Mit Hilfe der einheimischen Bulgaren restaurierte Kiril das seit 100 Jahren verlassene Kloster Lešok. Kiril widmete sich einer beträchtlichen Menge prediger, literarischer und pädagogischer Arbeit. Er eröffnete eine Schule und versuchte, eine Druckerei aufzubauen, überzeugt von der Bedeutung des gedruckten Buches. Kiril half später Teodossij Sinaitski bei der Restaurierung seiner 1839 abgebrannten Druckerpresse in Thessaloniki. Kiril Pejtschinowitsch starb am 12. März 1845 im Kloster Lešok und wurde dort beigesetzt.

1934 wurde das Dorf Burumli in der Provinz Russe in Bulgarien zu Ehren von Kiril in Pejtschinowo umbenannt. Zu seiner Ehren trägt auch ein Nunatak in der Antarktis den Namen Peychinov Crag.

Werke

Ogledalo

Ogledalo (zu dt. Spiegel) hat eine Predigtform mit liturgisch-asketischem Charakter. Es ist ein Originalwerk des Autors, inspiriert von der Kolivari-Bewegung (auch Filokalisten genannt) auf dem Berg Athos, die für eine liturgische Erneuerung innerhalb der orthodoxen Kirche auf dem Balkan kämpfte. Zu diesem Zweck verwendeten die Kolivari die gesprochene Sprache der Menschen, je nach Region, in der sie übersetzten und schrieben. Die wichtigsten Themen der Arbeit sind: die Bedeutung des liturgischen Lebens, die Vorbereitung auf das Heilige Abendmahl, der regelmäßige Empfang des Heiligen Abendmahls. Besonders wichtig ist seine Argumentation gegen den Aberglauben und zur Bedeutung des individuellen asketischen Lebens und der Teilhabe am liturgischen Leben der Kirche. Außerdem wird am Ende des Werkes eine Sammlung christlicher Gebete und Anweisungen, von denen einige von Kiril selbst verfasst wurden, hinzugefügt.[17][18][19]

Laut der Titelseite des Buches wurde es in einfacher und nicht literarischer bulgarischer Sprache Untermoesiens (bulgarisch препростейшим и некнижним язиком Болгарским долния Мисии) geschrieben. Es wurde 1816 in Budapest gedruckt.

Uteschenija greschnim

Pejtschinowitschs zweites Buch, Uteschenija greschnim (zu dt. Trost des Sünders), ist ähnlich wie sein erstes eine christliche Sammlung von Anweisungen – einschließlich Ratschlägen, wie Hochzeiten organisiert und wie diejenigen, die gesündigt haben, getröstet werden sollten, sowie eine Reihe von lehrreichen Geschichten.

Uteschenija greschnim war 1831 druckreif, wie von Kiril in einer Notiz im Originalmanuskript angegeben. Es wurde zum Druck nach Belgrad geschickt, aber dies geschah aus unbekannten Gründen nicht, und es musste neun Jahre später, 1840, in Thessaloniki von Teodossij Sinaitski gedruckt werden. Während des Drucks ersetzte Teodossij die ursprüngliche Einleitung von Pejtschinowitsch durch seine eigene, behielt aber dennoch den Text bei, der sich auf die Sprache des Werks als einfache bulgarische Sprache von Untermoesien, von Skopje und Tetovo (bulgarisch простїй Ѧзыкъ болгарский долнїѦ Мүссїи Скопсский и Тетовский) bezog.

Weblinks

Einzelnachweise

- James Franklin Clarke, Dennis P. Hupchick - "The pen and the sword: studies in Bulgarian history", Columbia University Press, 1988, ISBN 0-88033-149-6, S. 221 (...Peichinovich of Tetovo, Macedonia, author of one of the first Bulgarian books...)

- Developing cultural identity in the Balkans: convergence vs divergence, Raymond Detrez, Pieter Plas, Peter Lang, 2005, ISBN 90-5201-297-0, S. 178.

- Chris Kostov (2010) Contested Ethnic Identity: The Case of Macedonian Immigrants in Toronto, 1900-1996, Peter Lang, 2010, ISBN 3034301960, S. 58.

- Roumen Daskalov, Tchavdar Marinov (2013) Entangled Histories of the Balkans - Volume One: National Ideologies and Language Policies Balkan Studies Library, BRILL, S. 440, ISBN 900425076X.

- Kiril called his native dialect: most common and illiterate Bulgarian language. He mentioned on the title page of his book Ogledalo (Mirror, 1816), published in Budapest, that the book was written in simple Bulgarian, as opposed to the literary, archaic, version of Church Slavonic, because of the need and the use in the simplest and not literary Bulgarian language of Lower Moesia. Siehe: Sampimon, Janette. Becoming Bulgarian: the articulation of Bulgarian identity in the nineteenth century in its international context: an intellectual history, Pegasus, Amsterdam 2006, ISBN 90-6143-311-8, S. 119, S. 222;

- In Ottoman times the names “Lower Bulgaria” and “Lower Moesia” were used by the local Slavs to designate most of the territory of today's geographical region of Macedonia and the names Bulgaria and Moesia were identified as identical. Siehe: Drezov K. (1999) Macedonian identity: an overview of the major claims; S. 50, in: Pettifer J. (eds) The New Macedonian Question. St Antony’s Series. Palgrave Macmillan, London, ISBN 0230535798.

- The Ottoman conquest of the Balkans found regional names, well established among the local population, which had formed as a result of ethnic changes and the political state of affairs in the Middle Ages. The name Bulgaria was retained along with that of Lower Land, Lower Bulgaria or Lower Moesia, respectively, chiefly for the western territories, i.e. Ancient Macedonia. For more see: Petar Koledarov, Ethnical and Political Preconditions for Regional Names in the Central and Eastern Parts of the Balkan Peninsula; in An Historical Geography of the Balkans, edited by Francis W. Carter, Academic Press, 1977; S. 293-317.

- The origins of the official Macedonian national narrative are to be sought in the establishment in 1944 of the Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia. This open acknowledgement of the Macedonian national identity led to the creation of revisionist historiography whose goal has been to affirm the existence of the Macedonian nation through history. Macedonian historiography is revising a considerable part of ancient, medieval, and modern histories of the Balkans. Its goal is to claim for the Macedonian peoples a considerable part of what the Greeks consider Greek history and the Bulgarians Bulgarian history. The claim is that most of the Slavic population of Macedonia in the 19th and first half of the 20th century was ethnic Macedonian. For more see: Victor Roudometof, Collective Memory, National Identity, and Ethnic Conflict: Greece, Bulgaria, and the Macedonian Question, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2002, ISBN 0275976483, S. 58; Victor Roudometof, Nationalism and Identity Politics in the Balkans: Greece and the Macedonian Question in Journal of Modern Greek Studies 14.2 (1996) 253-301.

- Yugoslav Communists recognized the existence of a Macedonian nationality during WWII to quiet fears of the Macedonian population that a communist Yugoslavia would continue to follow the former Yugoslav policy of forced Serbianization. Hence, for them to recognize the inhabitants of Macedonia as Bulgarians would be tantamount to admitting that they should be part of the Bulgarian state. For that, the Yugoslav Communists were most anxious to mould Macedonian history to fit their conception of Macedonian consciousness. The treatment of Macedonian history in Communist Yugoslavia had the same primary goal as the creation of the Macedonian language: to de-Bulgarize the Macedonian Slavs and to create a separate national consciousness that would inspire identification with Yugoslavia. For more see: Stephen E. Palmer, Robert R. King, Yugoslav Communism and the Macedonian question, Archon Books, 1971, ISBN 0208008217, Chapter 9: The encouragement of Macedonian culture.

- “At any rate, the beginning of the active national-historical direction with the historical “masterpieces”, which was for the first time possible in 1944, developed in Macedonia much harder than was the case with the creation of the neighbouring nations in the 19th century. These neighbours almost completely “plundered” the historical events and characters from the land, and there was only debris left for the belated nation. A consequence of this was that first that parts of the “plundered history” were returned, and a second was that an attempt was made to make the debris become a fundamental part of an autochthonous history. This resulted in a long phase of experimenting and revising, during which the influence of non-scientific instances increased. This specific link of politics with historiography... was that this was a case of mutual dependence, i.e. influence between politics and historical science, where historians do not simply have the role of registrars obedient to orders. For their significant political influence, they had to pay the price for the rigidity of the science... There is no similar case of mutual dependence of historiography and politics on such a level in Eastern or Southeast Europe.” Siehe: Stefan Troebst, “Historical Politics and Historical ‘Masterpieces’ in Macedonia before and after 1991“, New Balkan Politics, 6 (2003).

- Because in many documents of 19th and early 20th century period, the local Slavic population is not referred to as “Macedonian” but as “Bulgarian”, Macedonian historians argue that it was Macedonian, regardless of what is written in the records. For more see: Ulf Brunnbauer, “Serving the Nation: Historiography in the Republic of Macedonia (FYROM) after Socialism”, Historien, Vol. 4 (2003-4), S. 161-182.

- Numerous prominent activists with pro-Bulgarian sentiments from the 19th and early 20th centuries are described in Macedonian textbooks as ethnic Macedonians. Macedonian researchers claim that “Bulgarian” at that time was a term, not related to any ethnicity, but was used as a synonym for “Slavic”, “Christian” or “peasant”. Chris Kostov, Contested Ethnic Identity: The Case of Macedonian Immigrants in Toronto, 1900-1996, Peter Lang, 2010, ISBN 3034301960, S. 92.

- Until the 20th century, both outside observers and those Bulgarian and Macedonian Slavs who had clear ethnic consciousness, believed that their group, which is now divided into two separate nationalities, comprised a single people: the Bulgarians. Thus the reader should ignore references to ethnic Macedonians in the Middle Ages and Ottoman era, which appear in some modern works. For more see: John Van Antwerp Fine, The Early Medieval Balkans: a critical survey from the sixth to the late twelfth century, University of Michigan Press, 1994, ISBN 0472082604 S. 37.

- Виктор Фридман, “Модерниот македонски стандарден jазик и неговата врска со модерниот македонски идентитет”, “Македонското прашање”, “Евро-Балкан Прес”, Скопје, 2003

- Блаже Конески, “За македонскиот литературен jазик”, “Култура”, Скопје, 1967

- Teodosij Sinaitski, Konstantin Kajdamov, Dojran, 1994

- Милан Ѓорѓевиќ, Агиоритското просветителство на преподобен Кирил Пејчиновиќ I (The Hagioretic Enlightenment of Venerable Kiril Pejcinovic), study, in: “Премин”, бр. 41-42, Скопје 2007

- Милан Ѓорѓевиќ, Агиоритското просветителство на преподобен Кирил Пејчиновиќ II (The Hagioretic Enlightenment of Venerable Kiril Pejcinovic), study, in: “Премин”, бр. 43-44, Скопје 2007

- Милан Ѓорѓевиќ, Верска VS граѓанска просвета. Прилог кон разрешувањето на еден научен парадокс, in: Православна Светлина, бр. 12, Јануар 2010