Shepard-Tische

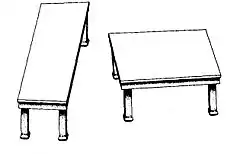

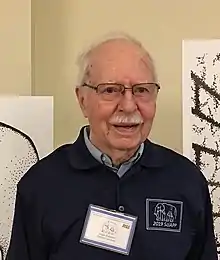

Shepard-Tische sind eine optische Täuschung, die Roger N. Shepard, ein Psychologe der Stanford University, 1990 mit der Bildunterschrift Tischedrehen („Turning the Tables“) in seinem Buch Mind Sights über die von ihm erschaffenen Wahrnehmungstäuschungen veröffentlicht hat.[1] Es ist eine sehr wirkungsvolle optische Täuschung, bei der die tatsächliche Länge meist um 20–25 % falsch geschätzt wird.[2][3]

Erklärung

In A Dictionary of Psychology werden die Shepard-Tische als ein Paar von identischen Parallelogrammen beschrieben, die die Tischplatten von zwei Tischen darstellen und deutlich unterschiedlich erscheinen, weil unser Sehsinn diese anhand der Regeln für dreidimensionale Objekte dekodiert.[1]

Die optische Täuschung basiert auf einer Zeichnung von zwei Parallogrammen, die – abgesehen von einer Rotation um 90° – identisch sind. Wenn die Parallelogramme durch das Hinzufügen von Tischbeinen als Tischplatten erkannt werden, sehen wir sie als Objekte im dreidimensionalen Raum. Ein Tisch erscheint nahezu quadratisch, weil wir eine Tischkante für perspektivisch verkürzt halten, der andere als lang und schmal.[4]

Die MIT Encyclopedia of the Cognitive Sciences erklärt die optische Täuschung als einen Effekt der Gleichmäßigkeit von Größe und Form, durch den die hintere Länge entlang der Sichtlinie subjektiv verlängert wird.[5] Sie klassifiziert die Shepard-Tische als ein Beispiel einer geometrischen Täuschung in der Kategorie Größenwahrnehmungstäuschung („Illusion of Size“).[5]

Nach Shepard bleiben das Wissen, das wir über optische Täuschungen haben, und das Verständnis, das wir auf intellektueller Ebene gewinnen, praktisch machtlos, um das Ausmaß der Illusion zu verringern.[6]

Überraschenderweise sind autistische Kinder beim Betrachten der Shepard-Tische weniger anfällig für die optische Täuschung als ihre Altersgenossen,[2] obwohl es bei der Ebbinghaus-Täuschung keine Unterschiede gibt.[7]

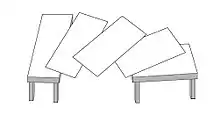

Shepard beschrieb 1981 eine frühere, weniger wirkungsvolle Version der optischen Täuschung als „Parallelogramm-Illusion.“[1]:S. 297–299 Die optische Täuschung kann auch mit identischen Trapezoiden anstelle von identischen Parallogrammen erzeugt werden.[8]

Eine Variante der Shepard-Tische wurde 2009 zur Optischen Täuschung des Jahres („Best Illusion of the Year“) gekürt.[9][10]

Weblinks

Einzelnachweise

- Andrew M Colman: A Dictionary of Psychology, 3. Auflage, Oxford University Press, , ISBN 9780191726828: „The illusion was first presented by the US psychologist Roger N(ewland) Shepard (born 1929) in his book Mind Sights: Original Visual Illusions, Ambiguities, and Other Anomalies (1990, p. 48). Shepard commented that ‘any knowledge or understanding of the illusion we may gain at the intellectual level remains virtually powerless to diminish the magnitude of the illusion’ (p. 128).“ Und: „a pair of identical parallelograms representing the tops of two tables appear radically different“ because our eyes decode them according to rules for three-dimensional objects.

- Philippe Chouinard: The Psychology of Seeing in Autism. LaTrobe University. Abgerufen am 11. Februar 2019: „[The Shepard tables] illusion is one of the strongest optical illusions that exists, on average the apparent size difference is 20–25%. Our preliminary work and earlier work performed by others (Mitchell, Mottron, Soulieres, & Ropar, 2010) reveal how susceptibility to this particular illusion is diminished considerably in persons with an ASD.“

- Christopher W Tyler: Paradoxical perception of surfaces in the Shepard tabletop illusion. In: I-Perception. 3, Nr. 3, 19. Mai 2011, S. 137–141. doi:10.1068/i0422. PMID 23145230. PMC 3485780 (freier Volltext). „One of the most profound visual illusions .. is the Shepard tabletop illusion, in which the perspective view of two identical parallelograms as tabletops at different orientations gives a completely different sense of the aspect ratio of the implied rectangles in the two cases (Shepard 1990).“

- Arthur Gilman Shapiro, Dejan Todorovic: The Oxford Compendium of Visual Illusions. Oxford University Press, 2012, ISBN 978-0199794607, S. 239: „For example, the famous Shepard tabletop illusion (Shepard, 1981) is more convincing when the planes are embedded in box shapes than when they are presented in isolation.“

- Robert Andrew Wilson, Frank C Keil: The MIT Encyclopedia of the Cognitive Sciences. MIT Press, 2001, ISBN 978-0262731447, S. 385–386: „size and shape constancy subjectively expand the near-far dimension along the line of sight to compensate for geometrical foreshortening.“

- RN Shepard: Mind Sights: Original visual illusions, ambiguities, and other anomalies, with a commentary on the play of mind in perception and art. W.H. Freeman and Company, 1990, ISBN 978-0716721345, S. 128: „Because the inference about orientation, depth, and length are provided automatically by underlying neuronal machinery, any knowledge or understanding of the illusion we may gain at the intellectual level remains virtually powerless to diminish the magnitude of the illusion.“

- , K. Royals: Illusion Strength and Associated Eye Movements in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder While Viewing Shepard and Ebbinghaus Illusion Displays. In: INSAR 2018 Annual Meeting. International Society for Autism Research.

- Susana Martinez-Conde, Stephen Macknik: Champions of Illusion: The Science Behind Mind-Boggling Images and Mystifying Brain Puzzles. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2017, ISBN 978-0374120405, S. 46: „Photocopy this page and then…cut around the trapezoid shapes…The effect is a version of the classic Shepard Tabletop illusion.“

- David Phillips: Shepard's tables – What's up?. OpticalIllusion.net. 14. Oktober 2009. Abgerufen am 10. Februar 2019: „Recently Lydia Maniatis pointed out a puzzling aspect of the illusion, in her prize-winning entry for the Illusion of the Year Competition.“

- Lydia Maniatis: Another turn: a variant on the Shepard tabletop illusion. In: Best Illusion of the Year Contest. 2009. Abgerufen am 10. Februar 2019: „The three pink- and blue-colored parallelograms are the same. All blue lines are equal in length; all pink lines are also equal. Box B is simply Box C rotated counterclockwise. But the three parallelograms look different, and boxes B and C look different.“